Investors, Know Thy Factors

As a long-term investor, one is always thinking about what factors drive your investment returns. Here we are not talking about the day-to-day gyrations of the market. Academics have proven that the market takes a random walk along its long-term path. Instead, we want to focus on the factors that will determine where the market will be in 5, 10 or more years. Unfortunately, sometimes investors focus on things that cause short-term volatility but actually have limited effect on long-term market returns. To help you make informed investment decisions, let’s look at which factors matter for long-term market returns and which don't.

Earnings

Four times per year investors wait on pins and needles for companies to release earnings reports. These reports provide an update on how the company has performed during the previous quarter. Investors track those very closely and managements conduct conference calls to go over the most recent results and provide their thoughts on the future.

Do quarterly earnings results matter? Yes they do! Earnings per share (or EPS), and in particular EPS growth, are a good predictor of long-term investment returns. Have you heard the adage " earnings drive stocks"? We invest in stocks because we expect their earnings to grow over time along with the whole economy, and preferably even faster than that. Earnings compound, and earnings that grow faster compound faster, which is the key proposition for investing in equities.

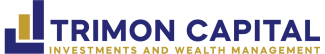

The chart below shows just over 31 years of history for the S&P500’s adjusted earnings index and its total return index on a quarterly basis. Both are indexed at 100 in March of 1993.

Source: Bloomberg, Trimon Capital

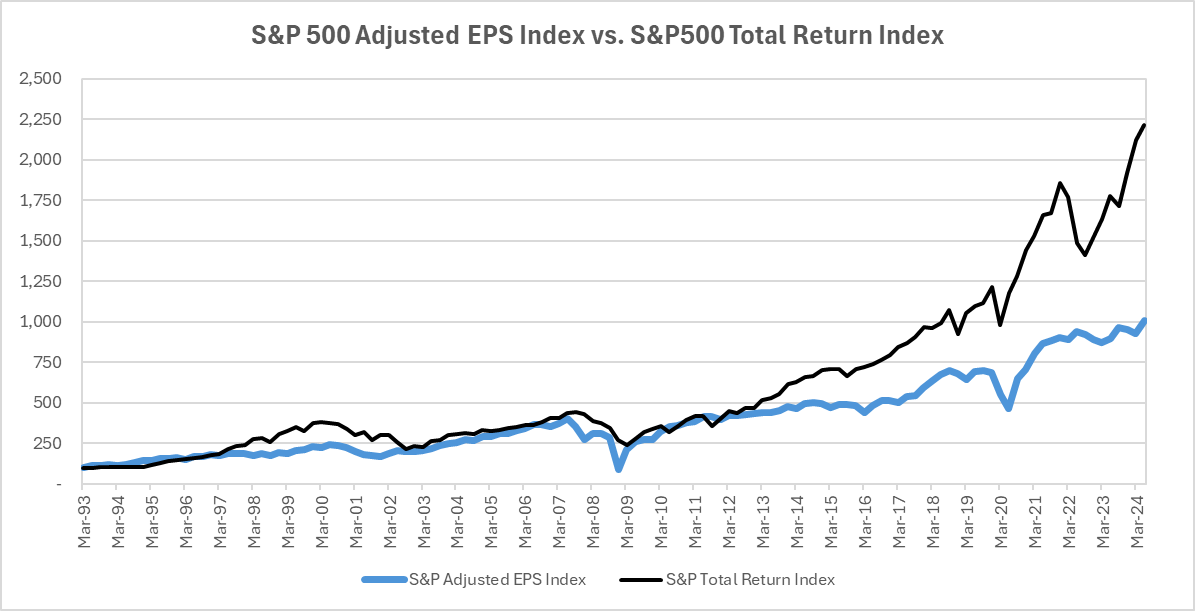

The more astute reader would notice the wide divergence between the two lines as of late. Does that mean the market has run ahead of fundamentals? While the above chart is interesting, it has one flaw: the increase in the absolute values over time due to the growth of the two variables skews the lines. A more useful chart to visualize the relationship between earnings and the market is one that takes the natural logarithm of the two. This is the chart below. We can still see the “hump” in market returns line during the dot-com bubble in 1998-2000, and there seems to be a slight divergence recently, but the magnitude is not that large.

Source: Bloomberg, Trimon Capital

That’s all fine, but why do we care about quarterly results if we invest for the long term? Because in the investment world the future is unpredictable and uncertain. The venerable long-term period consists of many short-term periods that compounded together will result in the realized long-term market return. The quarterly EPS reports provide confirmation that our expectations for the long term are still valid. If not, investors have to adjust their expectations, and, with that, share prices.

That said, investors are emotional crowd and sometimes tend to overreact to the most recent news or earnings reports. That may create buying or selling opportunities. The above explains why investors’ expectations matter so much, particularly in the short term. The market, as we know, is a forward-looking discounting mechanism. Investors try to anticipate the earnings trajectory for the next quarter, or next year, and price the shares accordingly.

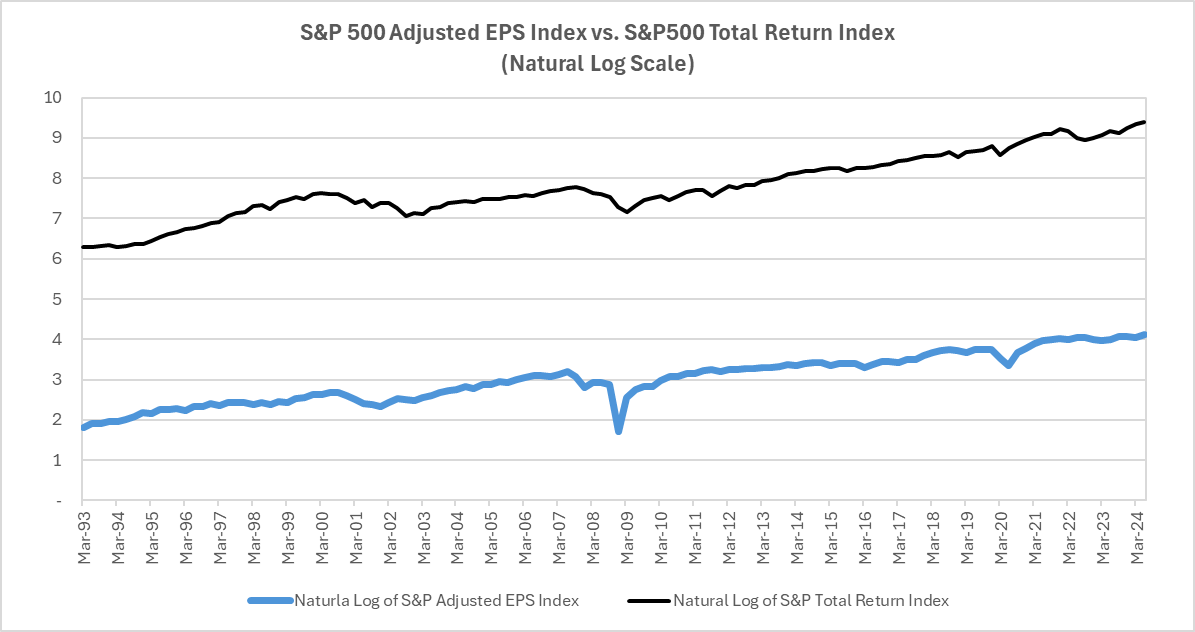

That's also why earnings growth does not always precede a rise in investment returns, and it does not always exactly match the latter, although they are both correlated over the long term. Looking at the S&P500 Index, we can see that earnings growth and market returns do not align perfectly.

Source: Bloomberg, Trimon Capital

To quote the exact numbers, for the period in question (3/1993-6/2024), the S&P500 provided an average annualized return of 10.6% per year, while the earnings grew on average by 7.7% per year. But one can see that there were three distinct periods during which EPS growth and market returns diverged significantly: 3/1993-6/2000; 6/2000-9/2011; and 9/2011-6/2024. So market returns and EPS growth can diverge for relatively long periods of time. Why is this the case? In order to answer, we need to look at another factor that drives long-term market returns.

Valuation

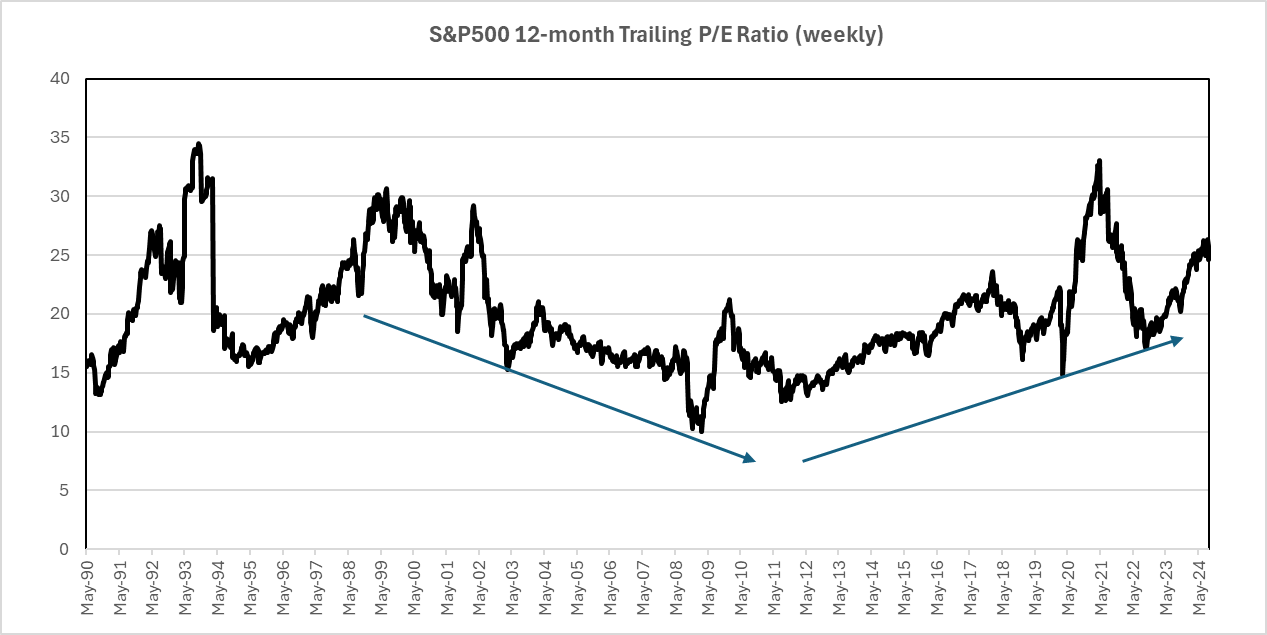

One of the most popular equity valuation metrics is the price-to-earnings ratio (P/E ratio, or P/E multiple). This is nothing but the inverse of earnings yield (or the E/P ratio). Intuitively, the higher the yield – the better, which means, the lower the P/E ratio – the better. When looking at the S&P500 index price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple over time, stocks can go through periods of extremely high or low valuations, but they are never sustained. As seen in the chart below, the 35-year average trailing (i.e. based on last 12-month EPS) P/E ratio for the S&P 500 is 16.4, and even though the market has fluctuated above and below this average, valuations always revert back toward the mean.

Source: Bloomberg, Trimon Capital

But even if we ignore the extreme valuations of less than 15x P/E and more than 25x P/E, a range of 15 to 25 is still rather wide. Consider the following: a move from 15x P/E to 25x P/E equals a return of +67% for the market, all else equal. Vice versa, a move from 25x P/E to 15x P/E equals a return of -40%, all else equal.

To put this into context, compare that to the annualized average return of about 10%. So a long period of “derating” (or decline of the P/E ratio) can negate EPS growth and result in mediocre market returns, as it happened between 1999 and 2012. Since then, we have seen a “rerating” of the market, i.e., an expanding P/E ratio. This results in market returns over and above EPS growth, as has been the case since 2012.

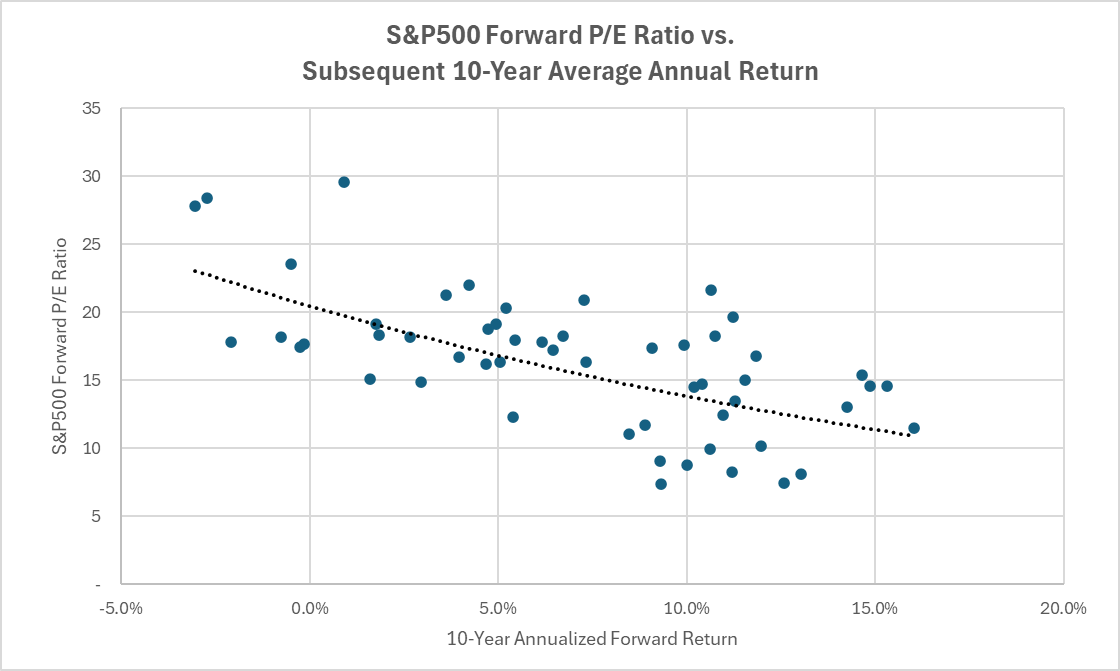

So the P/E ratio (or earnings yield) at which investors buy the market does matter for the long term returns. Below we show a scatter plot that relates the S&P500 P/E ratio vs. the average annualized return of the index over the forward 10-year period. There is a definite negative correlation between the P/E and the 10-year forward return.

Source: Bloomberg, Trimon Capital

To answer the obvious questions – the two leftmost points with 10-year average returns of -3.0% and -2.7% were for the periods ending in 2008 and 2009, respectively; while the rightmost point with 16% average return was for the period ending in 1998. So 1988 was a great year to buy stocks and hold them for 10 years. Where are we now? The current forward P/E multiple of the S&P500 is just under 21x, which historically has resulted in a pretty wide range of returns.

What causes these derating and rerating trends? The answer to this is beyond the scope of this note. But we can mention here factors such as risk-free interest rates, equity risk premium, and specific economic conditions (such as near-zero interest rates, the 2008 Financial Crisis, or the COVID pandemic) that cause valuations to deviate from their historical average.

Geopolitical Crises and Natural Disasters

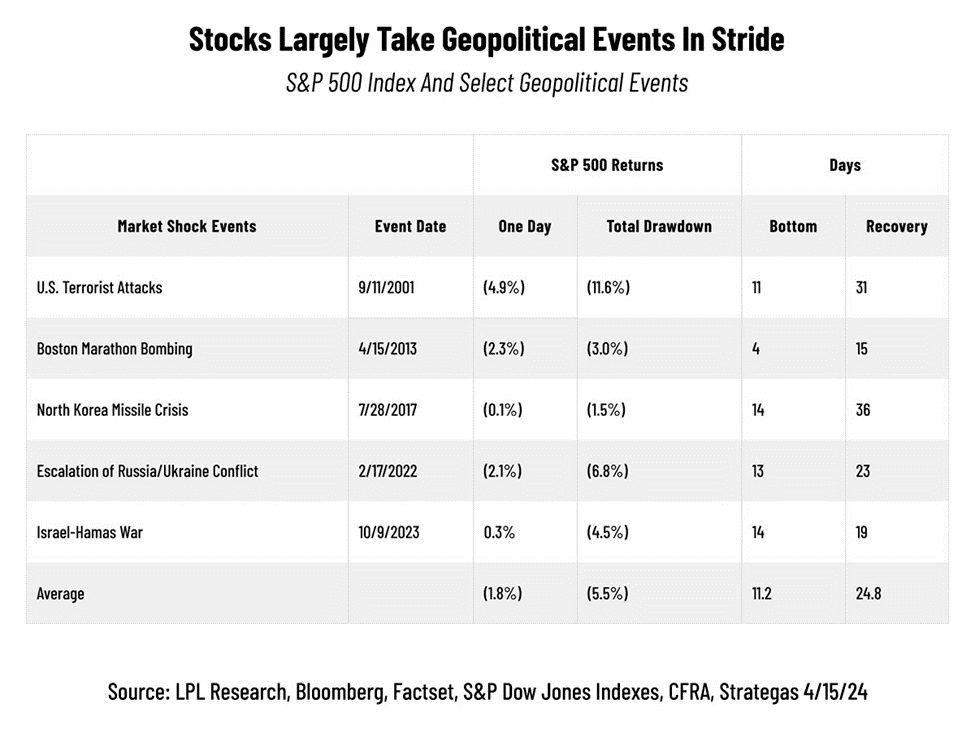

Regional tensions in Russia, the Middle East, and confrontation with China, are some of the recent geopolitical events that have been on the investors radar screen. One might think these fears are reason to be hesitant about one’s investments, but history shows that while these occurrences might cause temporary volatility, the market is very resilient to even rather negative geopolitical events.

The table below shows some of these recent events and the market reaction to them – the overall decline on the day and the time it took to recover the losses.

In the short term, the market tends to drop following a geopolitical crisis event, with the total average drawdown being in the low single digits. When looking at the long-term effects of such events, however, the picture gets decidedly better.

Looking over a longer period of time, the market has discounted events that were unlikely to have meaningful or long-term effect on earnings, while it has reacted more severely to events that might have affected the economy or the overall environment for stocks. For instance, one of the biggest one-day drops occurred following the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973 (-18.5%). The market did not recover, but declined a total of 25.5% over the following year. That was a severe shock to the global economy that altered the outlook for growth, inflation, and earnings. The other instance when the market did not recover, but declined, was the collapse of Bear Sterns in 2008. Even though initially the market took it in stride, it was down 38% over the following 12 months. That collapse caused a deflationary shock that, again, was rather negative for the economy and earnings. In pretty much all other instances the market took a short-lived drop, but carried on to provide positive returns in the subsequent month to a year period. So our conclusion is that investors should not overreact to geopolitical events or natural disasters that have no repercussions for earnings, and use those pullbacks as short-term buying opportunities.

So if you are an investor for the long term, do focus on the factors that have proven to matter and try to ignore those that don’t. The savvier ones among us may even use the occasional volatility and market pullbacks as buying opportunities, as long as the fundamental outlook for earnings have not been affected. It’s often easier said than done, but it’s worth trying. As always, caveat emptor!

________________________________________

This content is developed from sources believed to be providing accurate information. The information provided is not written or intended as tax or legal advice. Individuals are encouraged to seek advice from their own tax or legal counsel. Individuals involved in the estate planning process should work with an estate planning team, including their own personal legal or tax counsel. Neither the information presented nor any opinion expressed constitutes a representation by us of a specific investment or the purchase or sale of any securities. Asset allocation and diversification do not ensure a profit or protect against loss in declining markets.